Writing

The Inheritance

"The men in our family die young. Make the best of your time, son."

My father's eyes were bloodshot and wild, but determined, as he spoke the last words I'd ever hear from him. He never returned home that night, but to say he disappeared would be an untruth.

I will tell you my tale from the beginning, but let my story impress one thing upon you:

Do not waste your life's time.

My first memory is of my father placing a rough-hewn, wooden box on our dilapidated dining table. The dull "thud" of him dropping it onto the surface showed it was heavier than it looked. The look on my father's face made it seem doubly so, especially in the light of the candles nearby. Our house was fully modern and our power wasn't due to be shut off for another month, but I only received a meaningful stare when I asked why we couldn't use any electric lights.

I was five and had to stand on the matching wooden chair to get a proper view of the relic. The wood was stained to a near-black finish from handling, and it featured no clasp or hinges. In fact, at first glance, it appeared to be little more than an old timber block. Only by subtle, practiced motions was it revealed to be a modest container.

After a brief pause, my father reached into the box and withdrew a glossy photograph. He handed it to me without so much as glancing at it:

"This was our family, once. That was your mother, and the girl holding the baby- that's you- was your older sister. It was a moonless, summer twilight that stole them away from me. From US. I want you to know their faces before we leave this place. When we arrive in our new home, we will not speak of them again."

I accepted this easily, being a child and having little grasp of what I was being told at the time. I was told the sweet words that were whispered to me by excited parents and their daughter, and in wavering tones he revisited the lullabies that were sung when one of us couldn't sleep. I had no memory of these things, but I never forgot the evening where my father bared his heart to me.

When I asked where my mother and sister had gone, he took the picture back from me and returned it to the box. After another pause he whispered, "Just... gone," and closed the box again.

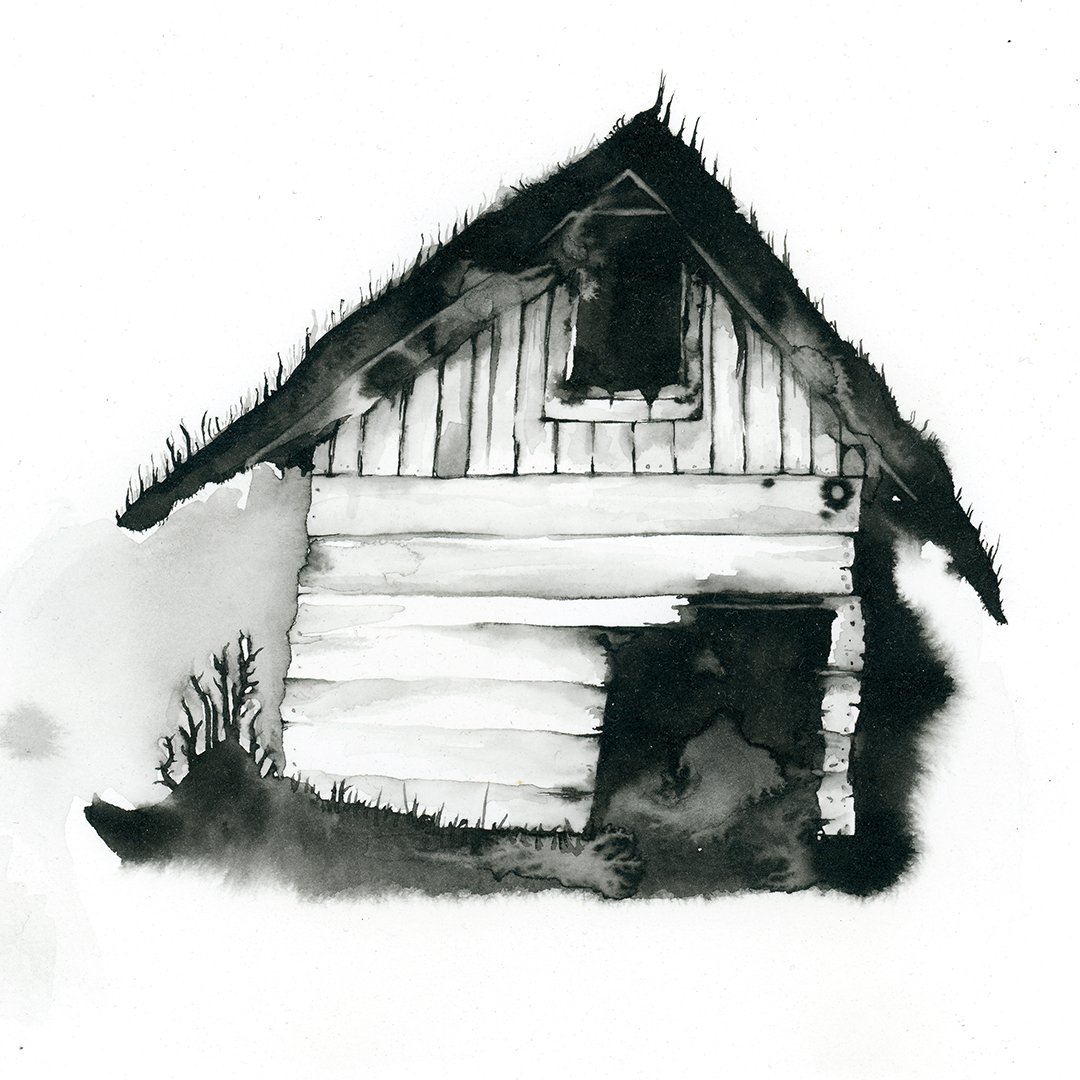

It wasn't long after that when we moved back to my father's childhood home. He said it had been in our family for generations and sat within a desolate corner of an old-growth forest much further north of where I had been living before.

It strongly resembled the box, much to my dismay. The inside revealed Spartan, wood furniture and an amateur attempt at plumbing fixtures where none had originally existed. There was no electricity, which meant no refrigerator. Most modern conveniences would be forgone, moving forward.

I learned a new way to live. My father called it "The Old Way."

Old things rarely appeal to young children, but we managed. We made only occasional visits to the small township that was closest to us, but even that was a day's journey by foot. We kept no animals, not even chickens. It remained just the two of us until the night of my thirteenth birthday.

That was when I met my grandfather.

He walked in through our door in complete darkness, unannounced and without a word, as my father sat down for my birthday dinner. He considered us expressionlessly before striding toward our table and coming to a stop.

He was a fearsome spectacle of a man and a mass of paradoxical qualities: Tall and gaunt, but strong and confident in movement. His hair was gray but long and thick, flowing down to the small of his back where he had pulled it into a tail. His skin was ashen in color as well, but not thin or blotched in elderly fashion. He moved in an awkward gait when he walked, yet made almost no sound where a stamp would have been expected. There was something unnatural about his posture that brought to mind sickness, despite giving no sense of him being ill.

He terrified me. Not due to these unsettling qualities, but because of his eyes. If a shark's eyes are empty voids, his were a sentient abyss. It was as though the whites of his eyes cowered into the corner of his perception, giving way to heavily dilated pupils lined with yellow-green. Nothing escaped them, it seemed to me, as they gave off sharp and unsettling reflections of candlelight.

My father stood and looked him in the eye, unflinchingly.

"Welcome to our table. This is my son."

The figure spared me only a brief glance before returning his attention to my father, and wordlessly seated himself at the table. He didn't eat, or drink, or speak for the duration of our meal. It wasn't until I had cleaned my plate that I had noticed how unnerved my father had become. Sweat was beading at his temple, but he returned grandfather's stare as if expecting something.

Bizarrely, the old man stood and without explanation turned and made for the door. When he reached the doorway, he looked back and addressed my father. His voice was little more than growl when he spoke, as though the effort were unfamiliar to him.

"Seven."

And then, without another sound, he was gone. I ran to the door to witness his departure, but he had already vanished. It was only then that I realized that the moon was full and hung high in the sky. How had grandfather, then, entered our home in complete darkness?

It wasn't until I looked to my father that I realized his face had gone pale and his eyes were wide and frantic. He whispered to himself, barely audible even as I strained to listen.

"Seven."

"Seven what, father?"

"Midsummers. It's time for bed."

Though we had no domestic animals to butcher, there was plenty of deer in the country. One adult doe would feed us for quite a while, though we also tended a modest garden that provided most of our herbs and vegetables.

Grandfather did not return in the immediate years following that night, and my father was almost tangibly reluctant to mention it. I can only think of one other occasion where he appeared so shaken as he did then.

It was my seventeenth year, and the growing season had been particularly bad and much of the local wildlife had left our area to search for food. By midwinter, our stocks had very nearly run out and the road leading to our nearest human neighbors was completely snowed out. I remember how desolate and quiet it had become, and how little distraction I had from the gnawing hunger that was becoming my steady companion.

I remember looking out the window and admiring the moonlight on the snow when I caught a momentary point of light in the distance, covered by darkness in rough brush. When I blinked, the point was gone, but a long shadow stretched from the edge of the forest toward our ramshackle cabin. It was twisted and unnaturally elongated to the point that I couldn’t tell what it was.

I refused to blink as I kept my stare fixed on the silhouette, but it made no movement whatsoever. The moments seemed to stretch into eternity until I could no longer refuse closing my eyes. I shut them tightly for only a moment before opening them again. The shadow was gone.

So was the moon.

As my eyes adjusted, the breath caught in my chest. Two perfect, thin, green rings shone dimly, halfway between the house and the forest edge. They remained perfectly still, suspended in the dark like a held breath.

After a moment, they vanished as disturbingly as they appeared. I ran to my father’s bed and woke him, pleading until he resentfully agreed to come to the window. We saw nothing but moonlight and a shadowless lawn.

A freshly butchered deer lay sprawled by our front door. When I reached for the knob to investigate, my father grasped me tightly by the wrist and stiffly shook his head.

“If it is there by sunrise, we will eat. Do not venture outside during a Blinking Moon.”

His hands were like ice, and wet with sweat. There was no request in his tone and no room for bartering, judging by the tremor in his voice. I waited, awake and aware, until morning when we finally retrieved the carcass.

We made every piece of the (until recently) healthy buck last until warmer weather broke, finally, a month later. It was two weeks before the flooding subsided enough for us to make our way to town to get supplies, and father was careful to travel by day only from then forward.

I had begun to believe that I had made the memory up and that the phantom lights were simply my imagination. It was possible that a mountain cat had caught the deer and was scared off by my appearance. The desperate winter may have driven it closer to our homestead than it had normally dared venture. It was the eyes catching an odd stray beam of light, surely.

In utter dark.

As midsummer approached, and my twentieth birthday drew closer, my father went to town without me to bring back the means to celebrate. He returned three days later, in the early evening. He apologized for taking the extra day, but he had waited to barter with a store-owner and night had crept up on him before he knew it. Home had been quiet, without even much wildlife making noise. The occasional bird would sing, or a squirrel would chatter, but the land seemed to be at rest and the peace was satisfying.

The night before my birthday, I asked father if he would like to go for a brief walk. He was distracted, which was unlike him.

“Is it the Blinking Moon?”

“What? No, son. Not that. Bring my box over and lay it on the table, and grab a lantern for more light.”

The thud as I set it down was exactly as I had remembered it. Instead of opening the box, however, my father beckoned me closer and showed me the secret to opening it. After showing me once, he had me do it two more times while he watched to make sure I had it memorized. When I moved to open the lid, however, he slapped his hand heavily on top of it with a smack that instantly caught my attention. The crack that broke the silence was still ringing in my ears as he spoke.

“This box is yours now, but what is within it is still mine. Do not open this until I have left this world. You will do this, without need for promise, because it must be done. Do you understand?”

I nodded, numbly, and my father’s mood immediately brightened.

“Let’s get ready for your birthday.”

The following day was one of my happiest memories that I will not share with you, now. It is mine and my father’s, but no one else’s. I will not cheapen it with repetition.

That evening, as the sun set in the trees, I sat down to a chocolate cake. I hadn’t had one since I was very little, but they had been my favorite as my father recalled. It explained the extra day; cocoa was hard to come by, even in town. The frosting was flavored with wild berries I had picked while he was away. The smell was intoxicating.

As my father sat across from me at the table, he placed two small candles in the top of the delicacy and lit them with a match. We do not sing songs on our birthdays, favoring quiet reflection and the occasional sweet. As I leaned forward to blow out the candles, the light of the full moon began to dim.

My father immediately tensed and turned to face the door. By the time I had turned my head, the moonlight had faded away entirely. A dark figure stood in our doorway, silently staring with unsettling yellow-green eyes.

The rough growl seemed even less human than before as it echoed in our house, and seemed to come from every direction at once.

“You will come, now. Follow.”

I turned to my father for answers and found him profoundly shaken and trembling. When I reached for him he motioned me away, however, never shying away from my grandfather’s terrible glare. For a tense moment, no person spoke or moved.

Then, for the first time, Grandfather turned his gaze on me. I could feel the fear he inflicted on me like a cold that seeps into the soul, and I knew he had truly seen me for the first time.

Before I had a chance to burst into a deluge of scared questions, my father took me firmly by the shoulders and looked me in the eyes. His face had been drained of all color, and an uncharacteristic horror dominated his expression.

"The men in our family die young. Make the best of your time, son."

Without another word, or even a backward glance, my father slipped through the darkened portal and into the unnatural twilight. I ran to the doorway, as I had when I was young, and I was not surprised to see that both men had gone. The moon shone brightly again.

Possessed and panicked, I searched the ground for any sort of trail by which I might follow them. None was left, regardless of how desperately I searched. I do not know how long I sought some sign of hope, but eventually I returned to the cabin, racked and tortured with fear and uncertainty.

As I reached the doorway, the forest echoed with an unearthly scream. It was brief, and shrill, and only vaguely human. It cut off, suddenly, and silence returned so quickly that it only served to unsettle me further. The quiet became heavy and pregnant with nefarious possibility, and when I could no longer bear to stare into it I closed the front door to my father’s childhood home. Alone.

I left that place soon after, before the days began growing too short to make good travel again. I brought little with me, just a few clothes and some food. The box, of course, I took as well. It wasn’t until I settled down with a woman and we had our first child, my son, that I dared open it several years later. Father had never told me to hide the box from anyone, but it seemed as though it was a vital secret. I only dared investigate once I was sure I was alone and the house was otherwise empty.

The glossy photo of my family was laid on top of dozens and dozens of other photos, artist portraits, or letters leading hundreds of years back in my father’s ancestral line. The picture of my family, and all other pictures for that matter, had suffered some staining. Oddly, these stains were almost uniform and circular, dark red, and placed precisely over the hearts of those represented. The stain over my father’s image seemed less dark, somehow, than the others. Mine was the only visage that remained untouched.

At the bottom of the pile rested a letter. It was badly damaged and nearly illegible, but appeared to describe a dispute between male neighbors over the killing of a mutual love of theirs. The writing was wild, obviously written in a rage, and some tears marked where the author had lost his temper and scratched through the paper.

The final half of the letter was almost completely illegible, except for the words “dark” and “feral”. I could only guess at what had happened to this man before replacing the box’s contents, closing it solemnly, and sliding it underneath the bed where I had been keeping it.

My wife never returned home that day. She vanished on the way to her car after work one evening, leaving me alone with my son. The authorities explained that the parking lot was dark and there was very little light, making it impossible to know what had happened. No sign of struggle, no other footprints, and the car was untouched. The case grew cold over the following weeks and was likely buried beneath mounds of similarly useless files in the back store room of the local precinct.

I took my son, close to five himself, and returned to the house that my father had raised me in. We arrived in early Spring, close to my son’s birthday, and I set to making my own improvements to my rundown inheritance.

On the evening of my son’s thirteenth birthday, the Blinking Moon brought Grandfather to my door. In the gloom he stared at me, unflinchingly, as he had done my father. As my child looked from one of us to the other, I realized that my grandfather had grown faintly younger in appearance. His hair was darker, his movements were more precise, and his body had been filled out with a light layer of extra muscle.

I was tempted to shout, but the words caught in my throat. After taking a shuddering breath, I finally spoke.

“Welcome to our table. This is my son.”

This time, the figure made no visible motion for some time.

“Six.” The word seemed to stick in his throat like tar.

When I blinked, he had gone.

“Six what, Dad?”

“Springs. It’s time for bed.”